A collection of war letters, from the Revolution to Iraq, helps us all share in the powerful dreams and fears of our soldiers and their loved ones.

7 Powerful Letters from Soldiers on the Front

When Andrew Carroll’s family home in Washington, DC, burned down in 1989, no one was hurt, thank God. But Carroll, then a sophomore in college, lost everything, including valuable letters from a friend who had witnessed the Tiananmen Square massacre in China.

A distant cousin, James Carroll Jordan, heard of the conflagration and called to check in. Carroll explained that everything had been lost, including those letters, which he recognized had historical relevance.

“Funny you should say that,” Jordan replied. “I was just going through my old World War II footlocker, and I came across a letter I wrote to my wife in 1945.” He mailed Carroll the letter, and what Carroll read changed his life.

Jordan was 23 and serving in Europe, though the war was pretty much over. Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower had just ordered nearby troops, including Jordan’s platoon, to enter a recently liberated concentration camp. “Ike knew there’d come a day when people would say, ‘It didn’t happen; it wasn’t that bad,’ ” Carroll, now 51, says. “He wanted eyewitnesses.” Upon his return from the camp, Jordan wrote an explicitly detailed three-page typewritten letter about what he witnessed at Buchenwald.

“Dear Betty Anne: I saw something today that makes me realize why we’re over here fighting this war,” it began. “We visited a German political internment camp. When we first walked in, we saw all these creatures that were supposed to be men. They were dressed in black and white suits, heads shaved and starving to death.” He mentions a monument that boasted of 51,000 deaths there in just three years. “They were proud of it.” He describes in rapid order “the building where they infected these people with disease …” “The torture dept …” “The 8 cremator furnaces …” He goes on: “There is another place I never told you about. The latrine. I won’t tell you about it, because you won’t believe me. It’s unbelievable.”

More than 40 years after Jordan recorded what he saw, his cousin was profoundly moved. “I was overwhelmed by the power of the letter,” Carroll says. When he called Jordan about sending it back, what Jordan said surprised him: “Keep it,” he told Carroll. “I probably would have thrown it away anyway.”

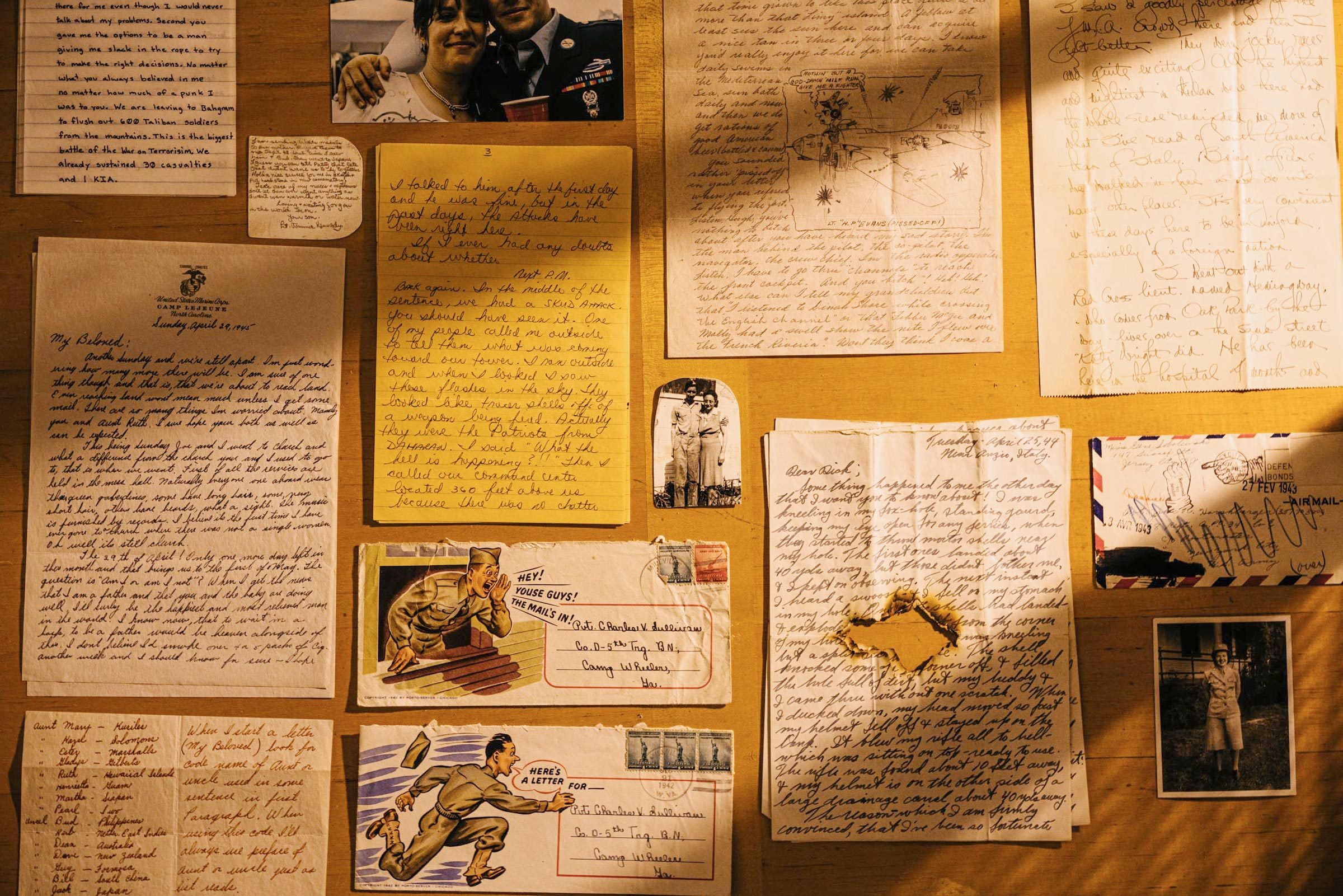

That statement shocked Carroll into action. He has spent the almost 30 years since then collecting the approximately 150,000 letters that comprise the Center for American War Letters at Chapman University in Orange, California. Many of the letters have come from the spouses of dead soldiers, who entrusted Carroll with their personal artifacts because they feared their own children or grandchildren would simply toss them out. Others were discovered by accident, in old barns, renovated homes, garbage bins, and flea markets.

They cover every major American war and battle, including Gettysburg and Pearl Harbor, and an equally wide array of topics. Some are routine, asking after Aunt Lettie or the farm. Others reveal raw emotion about lost time and mortality.

“We have so many letters of fathers writing to their newborn children,” says Carroll. “The explicit message is, ‘In case I don’t come home, know that your father loves you.’ ” Such letters, he says, remind us that America’s soldiers, sailors, airmen, and Marines also happen to be “someone’s child or parent. They’re not just statistics who go off to war.”

Still, imbued in many of the letters is a fervent love of country. One of the oldest in the collection dates back to the American Revolution. Its author, Alexander Scammell, explains to a friend why war against the crown must be pursued. The prose is eloquent and flowery, befitting the era in which it was written. But the substance is patriotism at its best:

“My friend, tyranny and oppression wield their iron rod over our country; they begin to shake the very foundation of our constitution. Whilst the voice of our forefathers’ blood cries to us from the ground, to define the rights, the liberty, and the territory which they so dearly purchased by their crimson gore and treasure … Every man of true honor & virtue will rather contend for the honor of first spilling his blood in so glorious a cause … yrs. Alexr. Scammell.”

A few years later, at the Battle of Yorktown, Scammell did indeed spill his blood for the cause he held so dear.

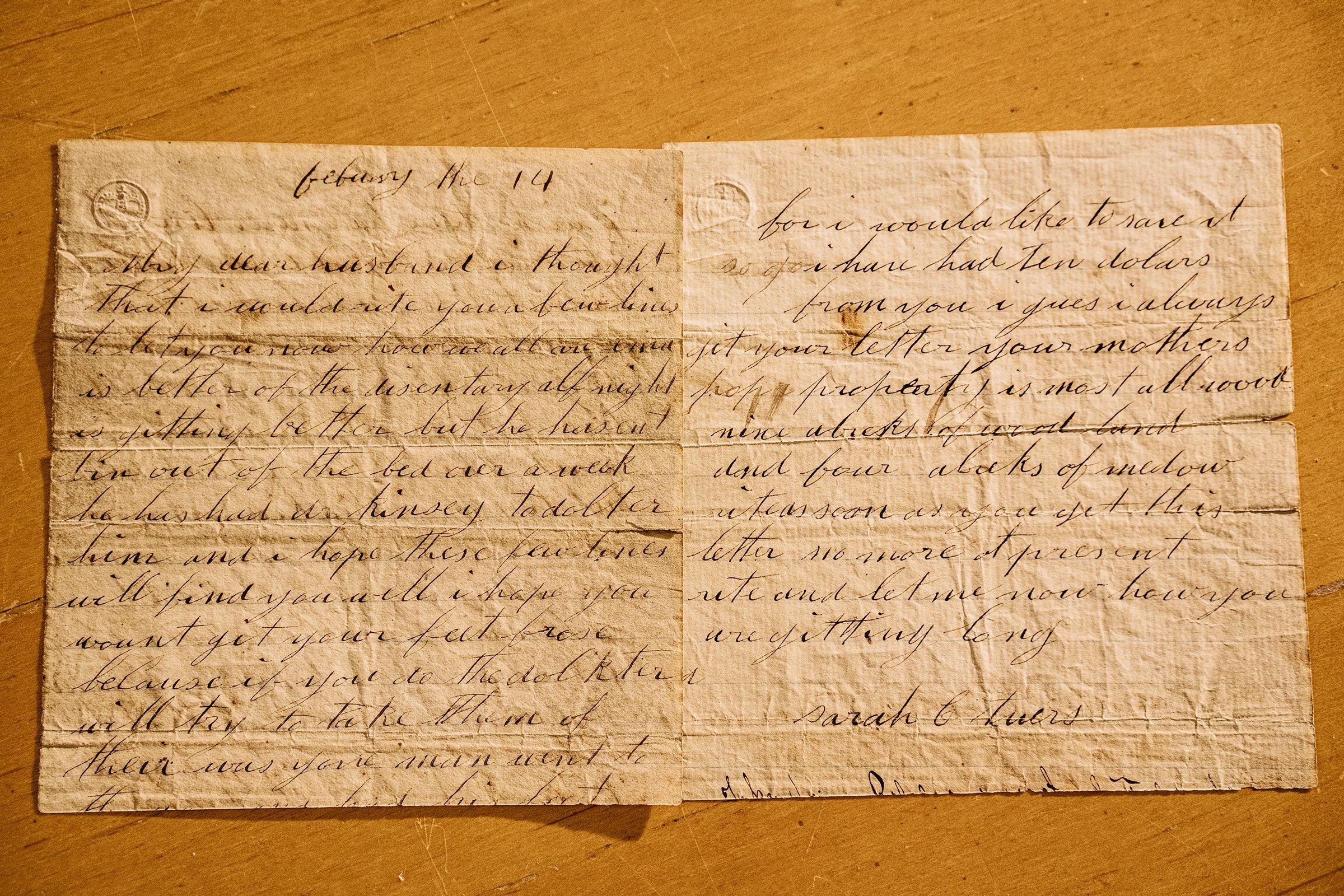

The Civil War

Filled with misspellings and a shocking observation about President Abraham Lincoln, this letter was written by the wife of a Confederate soldier on Valentine’s Day in 1863. It was taken off his body at the Battle of Chancellorsville by a Union soldier.

Most dear husband I thought that I would rite you a few lines to let you [k]now how we all are … i hope these few lines will find you well i hope you wont git your feet frose because if you do the dockter will try to take them of[f] … i wish their never had bin a lost war pitty old abe lincon hadnt dide fore he had took his seat [as president] o do try and take care of your self so that you will live to come home when i write this letter i cant help but cry of thinking of you … i have got the likeness [i.e., daguerreotype] framed this winter I have got that to look at if i hant got you but that don’t satesfy me for i would rather have you look at me rite as soon as you get this letter no more at present rite and let me [k]now how your gitting long sarah

World War I

Dated October 20, 1918—three weeks before Armistice Day—this letter was written by a young lieutenant to his wife. He’s in an Italian hospital for an ailment that’s never discussed. But he does mention a new friend who will become a household name in just a few years.

Dearest Sweetheart,

I was very very wicked this afternoon and went to the horse-races. They were jockey races and quite exciting. All of the highest and mightiest in Milan were there. Being officers, we walked in free as we do into many other places. It’s very convenient in these days to be in uniform, especially of a foreign nation.

I went out with a Red Cross Lieut. named Hemingway, who comes from Oak Park—by the way—lives over on the same street “Kathy” Wright did. He has been here in the hospital 4 months and has some time to go yet. He was out in the trenches one night when a trench mortar shell blew their cover away and left them exposed to machine gun fire. He got 247 wounds from the mortar shell and machine guns. He has a couple of pounds of metal they have carved out of him. Luckily he got most of it in his legs and not in a vital spot.

Your Buddy

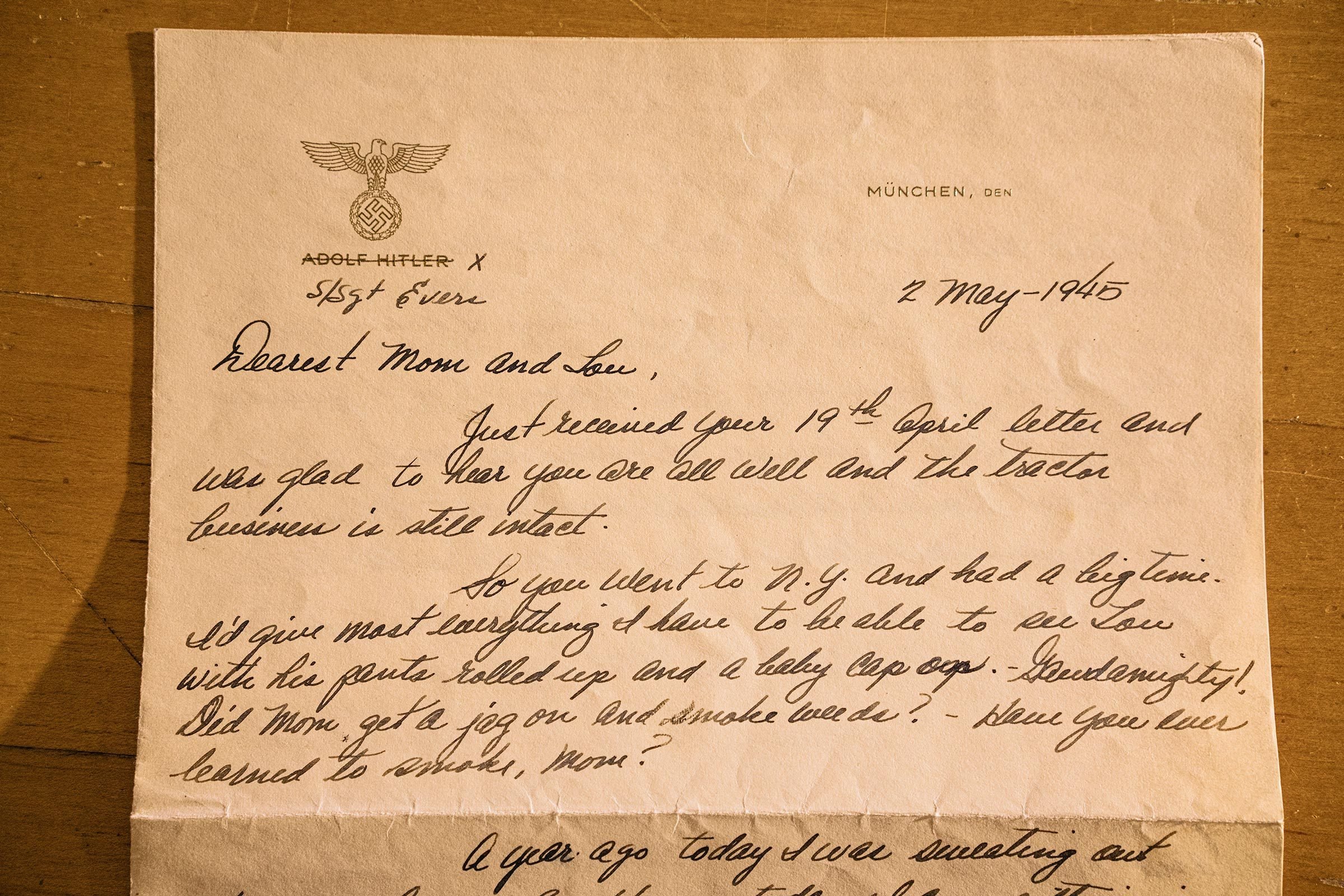

World War II

As this young lieutenant lay dying in a Japanese prison camp, he managed to scrawl some words on the back of two small photographs of his family and hand them to a fellow POW, who delivered them to his parents after the war.

Momie and Dad: It is pretty hard to check out this way without a fighting chance. But we can’t live forever. I’m not afraid to die, I just hate the thought of not seeing you again. Buy Turkey Ranch with my money and just think of me often while your there. Make liberal donations to both sisters. See that Bary has a car his first year. I guess you can tell Patty that fate just didn’t want us to be together. Hold a nice service for me … and put headstone in my cemetery. Take care of my nieces and nephews don’t let them ever want anything as I want even warmth or water now.

Loving & Waiting for you in the world be on.

Your son, Lt. Tommie Kennedy

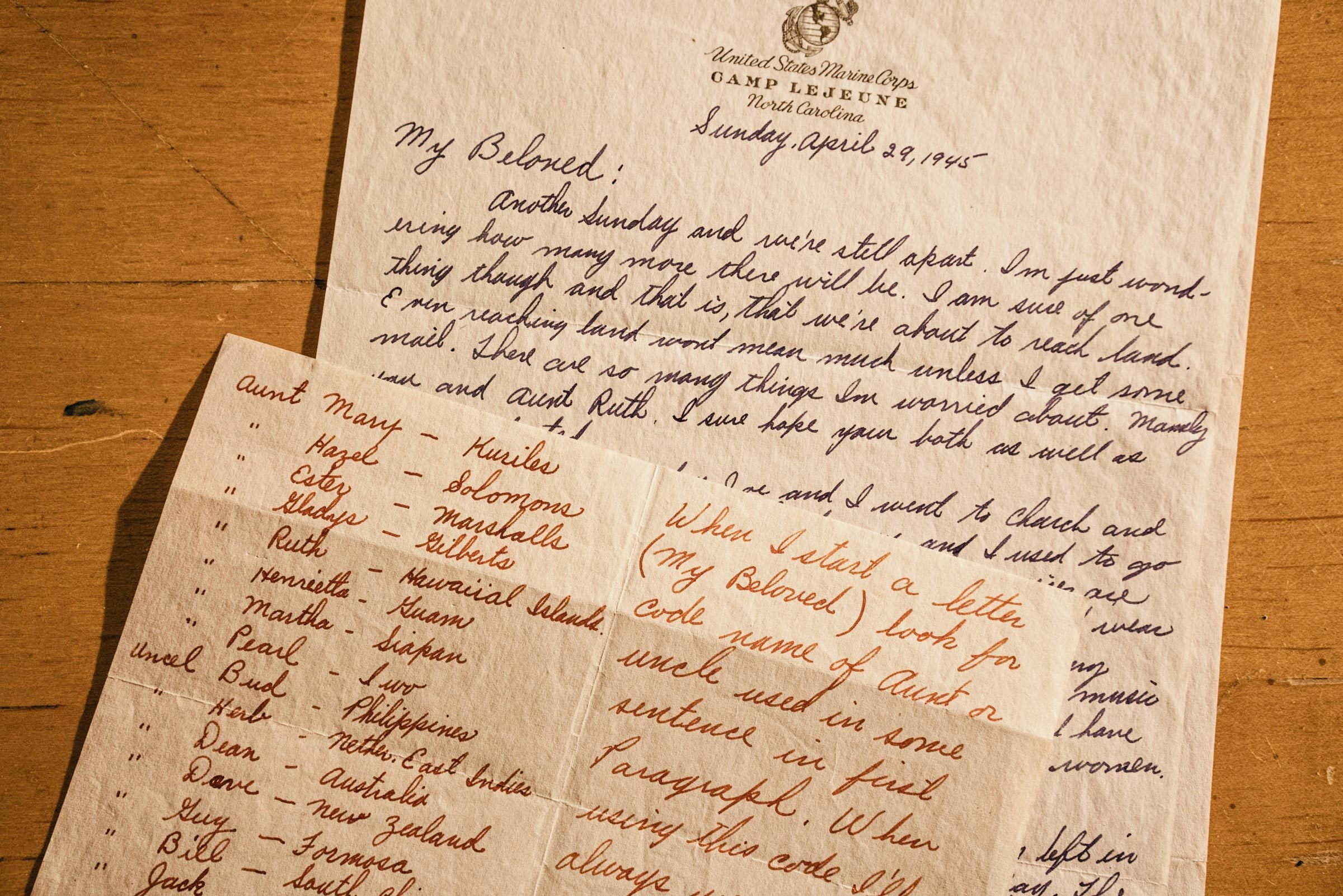

World War II

Many soldiers worried less about the battlefield than they did about the home front. This soldier, writing from “somewhere in North Africa” in 1943, overtly and covertly asks his girl back home if she still loves him.

Dear Dot,

Did you ever receive the perfume that I sent you? A tent mate sent some home after I did, and he has just received a letter acknowledging it. Perhaps you have too, but it might be in another batch of letters that are taking a long time to get to me.

Some letters ago I told you about the reactions of some of the men to news they received from home. It still keeps on happening and turns some of the boys into men. When the test comes, these will be the men who feel that they have very little to lose, and will become either heroes, or dead men.

This, my darling, is another one of those letters that started out as an exercise in two-fingered typing and became lost somewhere. I seem to hear you say, “Don’t be afraid, I’ll always understand.” You always have, so I keep pouring my petty troubles in your ears.

For me there is only one hope left, that at the end of my journey, you will be there to welcome me. All the love, darling, that I haven’t been able to give you for these many months has been choked up in my heart. Tonight I must tell you. You are the ship that will carry me safely home, the armor that will shield me from harm, and the breath that comes into my body. Every wonderful African sunrise is the light that shines from your eyes, and every sunset the curve of your lips. The lapping of the waves upon the shore was your voice whispering to me. There is nothing that is good and kind that crosses my path that doesn’t make me think of you. I’m hungry and thirsty, I’m tired and weary, I’m savage and beastly—I’m all that is wretched, only because we are apart.

You have created storms in my breast whose fury if unloosed would have torn us both apart. I loved you even when I thought I hated. I’m just trying to say what has been said a million times before by poets and singers and said so much better. Sweetheart, I love you.

Bill

Dot felt the same way Bill did. They married soon after he returned home. For more sweet stories, here’s how this veteran found his long-lost love after 75 years.

Korean War

This letter was found in the wastepaper basket in a bank, near the safe-deposit boxes. The writer, Paul, is addressing his “Dearest Wife & Family” from his hospital bed in Japan. He was wounded in the thigh by a sniper’s bullet during a fierce firefight with Chinese troops that saw many American casualties, including some who were wounded while helping Paul to shelter in a ditch. Because he couldn’t walk, the surviving Americans went off for help. Not long after, he “saw some guys walking against the dim light of the sky. I yelled for help and they started toward me; they had long fixed bayonets.” They were Chinese soldiers.

They squatted and stood around and looked at me for awhile but did not harm me or abuse me. In fact, I saw an honest look of pity and sympathy on every face. I knew then that they would not leave me there to freeze and die. They took me by the hands and tied a belt around my feet and dragged me for about a mile to a small burned out village. Then a Chinese medic came and put a fresh bandage on my leg and put me on a litter.

I was carried into the one house that was left standing where they made a warm fire and covered me up as best they could. I’m sure what they did for me saved my life.

Our 1st and 2nd battalions were coming through, and the Chinese had to leave. I opened the door and yelled for help. They [the Americans] heard me and found me. I thanked God!

I love you and have an idea that I will be seeing you soon.

P.S. What’s left of the squad would still like to have your cookies!

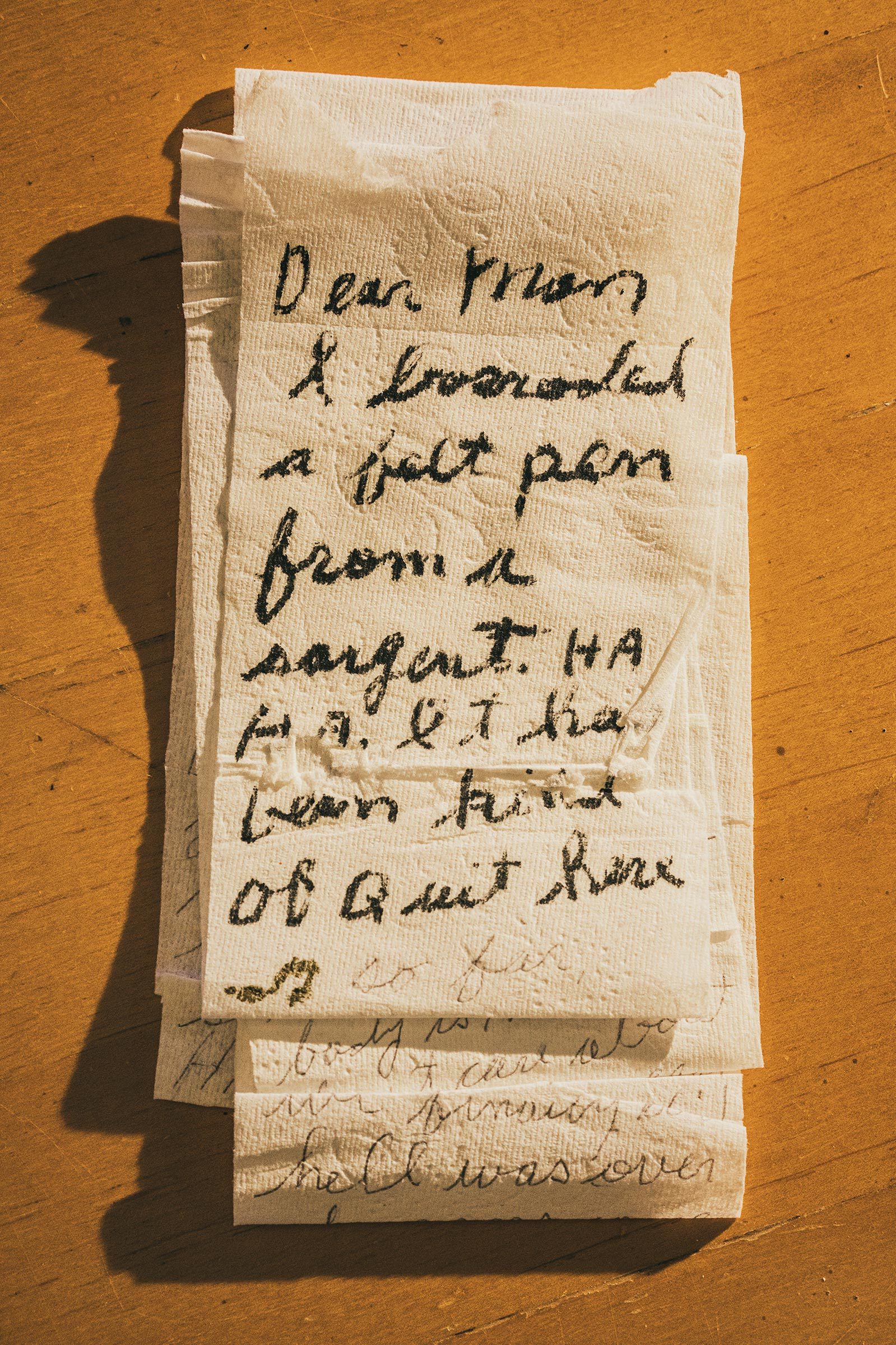

Iraq War

Service members often refer to one another using “call signs,” essentially nicknames inspired by a physical characteristic, a personality trait, or, in the case of second lieutenant Barbara “Heiny” Demetria, a single unfortunate incident that draws the attention of the chain of command, in this case, a future U.S. secretary of defense.

We were trudging over to the Combat Operations Center. General Mattis, as in the commanding general of the entire 1st Marine Division, had his back to the entrance. I was heading through the passageway when I felt myself slip. Almost in slow motion, I thought “Noooooooo!” as I tumbled—headfirst!—into his butt. Yes, my head; his butt. Now, every time I see him, I blush, and he smiles, thinking (I’m sure), “Yup, that’s the girl.”

Love, “Heiny”

Iraq War

This e-mail from Stephen Webber, a Marine serving in Iraq in 2004, was sent to his friends at St. Louis University, a Jesuit college in Missouri.

Over Christmas, my infantry battalion was activated and instead of going back to school, I am spending the spring in Iraq. I am between Fallujah and Baghdad, in the heart of the Sunni Triangle. These are random observations from my war. It is not complete. It will probably all change tomorrow. Forgive me if it’s not organized, living in the land of insanity makes it difficult to be coherent …

Twenty-some Iraqis were killed here yesterday by mortars at about 2 in the afternoon. The rounds landed about 650 feet from me. Today their relatives found out the names of the dead. [Carroll recalls Webber later telling him that he never did find out who fired the mortars.]

I sleep in a prison cell, literally. It was part of Saddam Hussein’s most notorious torture center. I eat breakfast where he killed 30,000 Iraqis over the last 10 years …

Yesterday a kid, who couldn’t have been any older than 4, pointed a stick at me like a rifle and pretended to shoot me. I wonder if someday my kids will meet him on some distant battlefield. I pray to God that if I have a son, he never has to go to war. That would tear my heart out.

I feel very bad for my family. I know that I am putting them through hell. Sometimes I feel guilty for not just studying abroad. If you get a chance, hug your mom for me. My mom is 9,000 miles and six months away. I would do anything to give her a hug right now. I miss her a lot.

I can’t speak for all, but for most of us it seems that our biggest concern is not getting killed but getting left behind.

It feels that everyone back in the world is getting on with their lives, finishing school, getting jobs or internships, making friends, planning their future—and we are frozen in time. When I get back, friends will be gone, innocence will be lost, and things will have changed. I just want things to be the way they used to be …

Stephen

Next, here are 33 patriotic Memorial Day quotes for every American.