My wife was having an asthma attack, so she took herself to the emergency room. Why was she left to die just outside the hospital doors?

My Wife Was Within Steps of the ER Door, But She Was Left There to Die

In November 2017, we published an article called “Thank You for Caring So Much,” a man’s letter of appreciation to the hospital workers who tried to save his wife from a devastating asthma attack. But it turns out there was much more to the story than he knew at the time.

In November 2017, we published an article called “Thank You for Caring So Much,” a man’s letter of appreciation to the hospital workers who tried to save his wife from a devastating asthma attack. But it turns out there was much more to the story than he knew at the time.

* * *

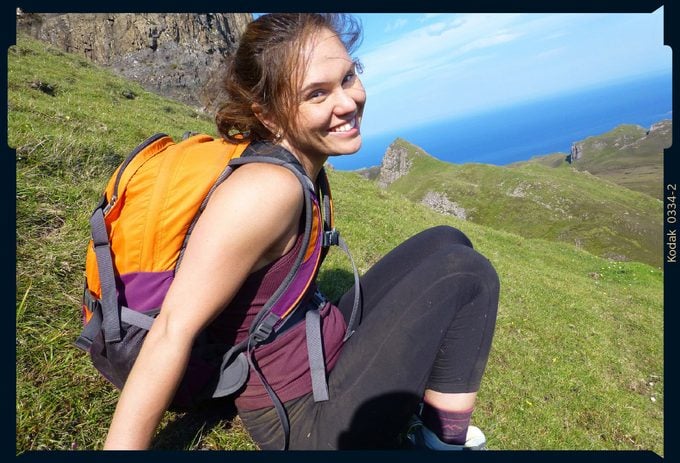

Laura Levis, the love of my life, died on September 22, 2016. She was just 34.

I was told that Laura never made it to the emergency room. That she collapsed on a street leading to CHA Somerville Hospital in Somerville, Massachusetts, or possibly in a parking lot on the outskirts of the property. My wife had called 911 just after 4 a.m., before she lost consciousness. She wasn’t able to give her exact location, they told me, so it took emergency responders a long time to find her. “She was in the last place they looked,” someone said. Even though that place was heartbreakingly close.

Some ten minutes passed between the time Laura called 911 and the time she was found, in cardiac arrest following an asthma attack. Those ten minutes meant her life.

People, of course, die from asthma, a disease that affects 19 million adults and 6 million children in the United States. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, more than 3,500 succumb to attacks each year, though in Laura’s age-group the death rate is less than 1 in 10,000 asthmatics. It’s especially rare in those as healthy and active as she was.

Laura worked out six days a week and competed in powerlifting competitions, where she could bench-press more than she weighed. Her asthma never impeded her. Laura was vigilant about carrying inhalers. Boxing up her clothes, I found more than 20 of them, in pockets, in purses, in gym bags.

On rare occasions, when an attack intensified, I would drive Laura to Mount Auburn Hospital in Cambridge, where she would be given prednisone, a nebulizer treatment, or both. We always arrived in plenty of time.

But I wasn’t with my wife that September day. And the reason for that, I’ll have to live with forever. At the time Laura collapsed, we were spending some time apart. We were seeing a couples counselor and had been in daily contact with each other. We had dinner plans the day she collapsed and were going apple picking that weekend, but we had slept apart the night before. She’d stayed, as fate would have it, in an apartment just a few blocks from Somerville Hospital.

I blamed myself for not being with her when the attack struck, for not being able to help my wife in that moment. I asked God, Why? Why?

Why?

One day I would receive an answer.

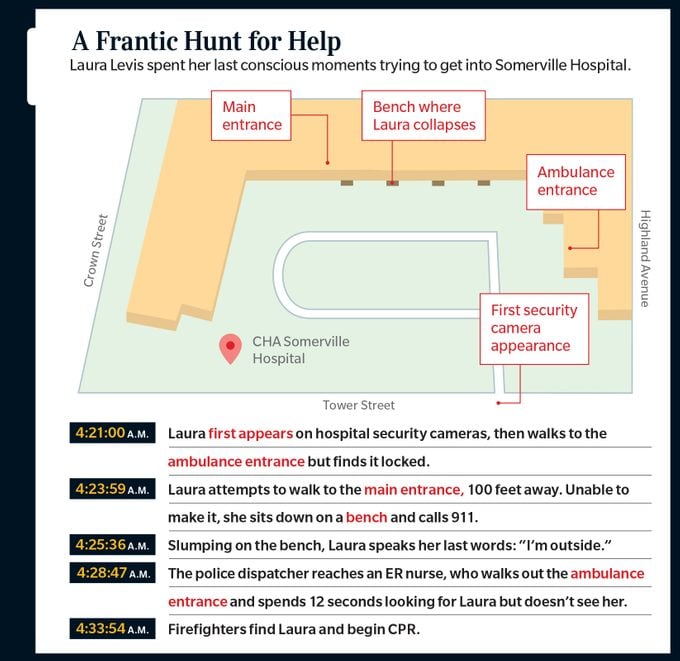

Somerville Hospital sits on a hill, with its emergency room at the very top. Dressed in purple sneakers, jeans, and her favorite hoodie from a Spartan Race we ran together, Laura began walking up the hill that morning in the midst of her attack. It’s about a 375-foot walk up Tower Street. Surveillance cameras first caught sight of her at 4:21 a.m.

Somerville Hospital sits on a hill, with its emergency room at the very top. Dressed in purple sneakers, jeans, and her favorite hoodie from a Spartan Race we ran together, Laura began walking up the hill that morning in the midst of her attack. It’s about a 375-foot walk up Tower Street. Surveillance cameras first caught sight of her at 4:21 a.m.

When Laura arrived at the hospital, she found a semicircular driveway and two entrances about 100 feet apart. Between them were four waiting benches, each with a flat stone top.

Signs pointing to the emergency room had led Laura up the hill, but inexplicably, neither entrance was adorned with an illuminated emergency room sign. With no clear indication of where to go, Laura had to choose one door or the other.

On the surveillance video, she pauses, then chooses the entrance on the right. As she approached it, she could see an emergency room waiting area through plate glass windows. She stepped in front of the automatic door, but it did not open. Surprised, she put both hands on the door and peered inside. But there was no one in sight.

Panic can accelerate an asthma attack by causing airway muscles to tighten, constricting airflow even further. Finding the door locked, Laura almost certainly panicked.

Maybe that is why she didn’t comprehend the instructions posted on the door, explaining that it was for ambulance access only. To enter the emergency room, patients needed to use the main entrance—the door to the left. The door she had not chosen.

Or perhaps she did notice those instructions. In the video, Laura turns and begins walking toward the main entrance. She didn’t make it there.

She walked past the first two waiting benches. But when Laura reached the third bench, just 29 feet from the main entrance, she sat down. The attack had become so intense, she could not walk those extra 29 feet. But she could still think clearly: She called 911.

Her voice on the phone with the dispatcher is filled with fear.

“I’m at Somerville Hospital” were Laura’s first words. “I’m having an asthma attack. I’m dying.”

“I’m at Somerville Hospital” were Laura’s first words. “I’m having an asthma attack. I’m dying.”

“Whereabouts are you at the hospital?” asks the 911 operator.

“Emergency room,” Laura responds. “I can’t get in.”

In just 41 seconds, she managed to relate seemingly everything the operator needed to know. Laura said she was having an asthma attack, one so severe that she felt she was going to die; she said she was at Somerville Hospital, outside the emergency room, and couldn’t get in. Laura was an amazing communicator—a journalist—and, with her life on the line, she didn’t waste a single word. If only she had been talking to the right person.

Laura’s cell phone call was routed to a regional 911 operator. The operator, sitting in a Massachusetts State Police operations center some 18 miles away, was merely a call screener who couldn’t send help. When Laura finished speaking, the operator told her to stay on the line as she connected Laura to the local police.

When the police picked up, a new operator asked her to explain all over again what her emergency was. But by then, she could barely speak.

“She’s outside of the Somerville Hospital,” said the regional operator, jumping in. “She’s having an asthma attack. She can’t get into the hospital.”

It should have been so easy for the two operators to locate Laura, since both had her cell number. A satellite ping of her GPS coordinates provided by her carrier would make Laura a digital dot on their computer-screen street maps. But, as can be the case with cell phone 911 calls, her location on their screens was wrong.

When you use an app involving your location, your phone constantly transmits where you are, like a homing beacon. But when you make a 911 call, that doesn’t happen. Instead, a satellite must be pinged, and that information is integrated with other bits of data to trace where you’re calling from, a more complex and often inexact process.

Laura’s ping registered at 68 Tower Street, a street corner some 200 feet from the hospital’s front door. Somerville’s police dispatcher asked Laura to clarify where she was. “Ma’am, where are you located there? You’re the one—you’re at 230 Highland Avenue, right?”

Laura’s ping registered at 68 Tower Street, a street corner some 200 feet from the hospital’s front door. Somerville’s police dispatcher asked Laura to clarify where she was. “Ma’am, where are you located there? You’re the one—you’re at 230 Highland Avenue, right?”

That’s the hospital’s official mailing address, on a completely different side of the building. But it was the only address the dispatcher had.

It would have been the perfect moment for the original 911 operator to have relayed more information, such as the fact that Laura twice said she was outside the emergency room, or that she twice said she was dying. But that operator had already hung up.

In the 911 tape, you hear Laura’s voice again. “I’m outside,” she starts to say, before struggling to make another sound. It is 4:25 a.m. and 36 seconds.

It is the last time Laura speaks.

It was the moment her life hinged upon. Within a minute or so, her heart would stop beating, and oxygen would stop going to her brain.

On the surveillance video, about 30 seconds later, Laura slumps on the stone bench, her arms falling to her sides. A glowing object, her cell phone, falls to the ground.

And then … stillness.

It’s unclear how long it takes your brain to die without oxygen, though there are some estimates based on medical research. After three minutes or less, you might fully recover. Between three and six minutes, your chances drop—but still, recovery can be possible. Beyond six minutes, there’s little chance your brain won’t be severely damaged, with death a much more likely outcome.

Laura’s countdown probably began a few seconds after 4:26 a.m., although it’s possible her heart kept beating for another minute after she lost consciousness, according to asthma experts. Every second was vital. Yet so many would be wasted.

After realizing Laura couldn’t speak anymore, the Somerville police dispatcher told her to hold while she called an ambulance. That took more than a minute—a minute that Laura would never get back.

The police next called the Somerville Fire Department, which has a station just 1,000 feet from the hospital. But the police dispatcher merely related that Laura “must be on Tower side,” failing to say that her cell phone pinged at 68 Tower Street, at the top of the hill, or that she was outside the emergency room. Without those details, the fire department’s dispatcher had to guess where Laura was.

Following a hunch, he sent his crew to the other side of the hospital, where an entrance to some doctors’ offices is locked overnight: “Attention Engine 7. Respond to the Somerville Hospital, 230 Highland Avenue … We believe this is possibly on the Medical Arts Building side.”

Somerville Hospital is the last to be reached by phone. There is no direct line to the emergency room, apparently, even for police, so a night receptionist had to patch the call through. The transfer took about 30 seconds—more time wasted.

Somerville Hospital is the last to be reached by phone. There is no direct line to the emergency room, apparently, even for police, so a night receptionist had to patch the call through. The transfer took about 30 seconds—more time wasted.

Finally, nearly two minutes after Laura had lost consciousness, a phone in the emergency room rang. A nurse, whom I’ll call Nurse X, answered.

“Hi, it’s Somerville Police. Are your doors locked, by any chance?” said the dispatcher.

“No. Why?” responded Nurse X.

“Because there’s a female who’s having an asthma attack … She’s pinging off Tower Street, and she’s saying the emergency room is closed. So I don’t know where she is,” the dispatcher continued.

“I’ll go look,” said Nurse X.

Hanging up, she walked to the ambulance-access door, which she found locked, and opened it. On the surveillance video, you see Nurse X take one step outside, craning her neck as she peers into the predawn darkness. Laura was just about 70 feet from her. But the bench where Laura collapsed is not well lighted, so Nurse X does not spot her. She hovers at the door for 12 seconds, going no farther, before returning inside.

It would have been easy for hospital security to have seen Laura on camera, but the desk had been left unattended, as both officers on duty were needed for patient watches inside the emergency room. Nurse X sees those officers when she returns but does not tell them about Laura. Instead, she calls the Somerville Police back.

“I looked outside up here, but I didn’t see anything,” she told the dispatcher. She offered to call Laura’s cell phone. Seconds later, on the surveillance video, you see Laura’s phone light up on the ground. But she cannot answer it, and it goes dark.

Failing to find Laura at the doctors’ office doors, Engine 7’s crew headed up the hill on foot. Firefighter David Farino was the first to spot Laura, rushing to her and ripping her hoodie in two to start CPR. But he was too late.

Farino had taken only three minutes to walk up Tower Street. But those three minutes pushed the time Laura had gone without oxygen to her brain to upward of seven minutes, and while a heart can be restarted at that point, as hers was, people rarely survive.

Laura was at last brought inside the emergency room some 15 minutes after she’d called 911. It wasn’t until hours later, at 7:15 a.m., that someone from the hospital called me and told me that Laura had collapsed. When I got there, no one could tell me a whole lot more. The night shift that had restarted Laura’s heart and put her on life support was no longer on duty.

We spent seven days in the ICU at CHA Cambridge Hospital, Somerville’s sister hospital. During all that time, I barely left my wife’s bedside. No one mentioned anything to me about Laura making it to the doorstep of Somerville’s emergency room. Even a month later, after the New York Times published my thank-you letter, no one had said a word to me about Laura being outside that door. And maybe they never would have.

But the circumstances surrounding Laura’s death deeply bothered her uncle, Robert Levis. Uncle Bob called the Somerville Police to ask whether there was a police report that could help explain what happened.

I’d been told that there would be no report, as officers didn’t write up medical calls. But Detective Michael Perrone and his fellow officers were so deeply moved by Laura’s death that they broke protocol. They interviewed the firefighters who had found Laura and one of the guards on duty that night and viewed surveillance footage from the hospital’s cameras, describing all they observed in writing, in case that footage was ever erased.

Uncle Bob shared the report with Laura’s dad, Dr. William Levis, a former officer with the U.S. Public Health Service. I will never forget my father-in-law’s voice cracking apart when he called me. “Pete, I have the most terrible thing to tell you,” he said. “They killed Laura.”

Uncle Bob shared the report with Laura’s dad, Dr. William Levis, a former officer with the U.S. Public Health Service. I will never forget my father-in-law’s voice cracking apart when he called me. “Pete, I have the most terrible thing to tell you,” he said. “They killed Laura.”

Through numerous letters and phone calls, I obtained the grainy, horrible surveillance video showing Laura outside the hospital. I obtained from the state police the shattering recording of Laura’s 911 call. I sought out every document I could find: police and fire reports, ambulance reports, state investigators’ reports, field notes from hospital inspections, and internal hospital documents, which I requested through the Freedom of Information Act. And I spoke with lawyers at the largest medical malpractice firm in Boston.

Suing Somerville Hospital would not give Laura the chance to live her life, to be a mother, to grow old with me. Still, if its owner, Cambridge Health Alliance, was made to pay millions in damages, it would potentially send a message to hospitals across the country to reevaluate their emergency room procedures. By making the hospital pay, I thought, maybe Laura’s death would stand for something.

The Massachusetts Department of Public Health turned up more patient-safety violations at Somerville Hospital, citing it for failing to provide a safe environment and for “poor quality of pre-hospital care.”

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services accused Somerville Hospital of violating federal law by denying Laura access to emergency care. Officials agreed to pay $90,000 to the government in a settlement.

But my hope of making the hospital pay went no further than that. In Massachusetts, a law protects public hospitals from being sued for more than $100,000 and indemnifies their employees, even in cases of wrongful death. Without the cap, we’d likely be looking at a multimillion-dollar verdict, assuming we won. With the cap, Laura’s death, in the eyes of the law, hardly seemed to matter.

But how could her death not matter? How could I go on living if Laura’s tragedy changed nothing? And so I began writing her story.

The Federal Communications Commission estimates that 10,000 lives could be saved annually if emergency responders could get to 911 callers just one minute faster, and that figure could be vastly conservative. What can be done to save those lives, to make sure that no one else dies the way Laura did?

There are a number of possible solutions.

For one, I hope that regional 911 call centers become a thing of the past. Had Laura’s call gone directly to the Somerville Police Department, I am convinced that a local dispatcher, familiar with the hospital, would have asked Laura whether she was at the top or bottom of that hill. It isn’t just my view—911 calls misrouted to wrong call centers are a national issue.

Millions of 911 cell phone calls register inaccurate locations each year, because of tree interference, poor atmospheric conditions, and other challenges, per the National Emergency Number Association. Locations are so often wrong that, according to one survey, 82 percent of 911 operators doubt the location information they receive. Incredibly, Laura’s location would have been considered “accurate” according to FCC standards, even though it led first responders astray.

A push is underway for states to adopt the Next Generation 911 system, in which callers will be able to send text messages, photos, and video to help emergency responders locate them and assess their crises. With such a system, Laura conceivably could have sent a photo of the ambulance-access door to her 911 operator, who in turn could have texted it to Engine 7’s crews, or even to Nurse X.

Thanks to software upgrades, Android and Apple phones can now automatically relay a 911 caller’s coordinates to the operator. The location readings can still be off by hundreds of feet, but they are more frequently leading responders to almost the exact location. Far more needs to be done by mobile service providers and regulators to improve the system, but at least some progress is being made.

Medical errors have become the country’s third-leading cause of death, resulting in as many as 250,000 deaths per year, according to a study by Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. Another study estimates the number could be as high as 440,000.

In Laura’s case, something as simple as requiring two people to conduct a search—a second set of eyes—could have made the difference. Doctors and nurses can reduce commonplace errors simply by reminding themselves never to skip a single step in whatever they’re doing—such as walking 100 feet between two doors, just to make sure no one is there.

In Laura’s case, something as simple as requiring two people to conduct a search—a second set of eyes—could have made the difference. Doctors and nurses can reduce commonplace errors simply by reminding themselves never to skip a single step in whatever they’re doing—such as walking 100 feet between two doors, just to make sure no one is there.

The same goes for those with medical conditions, particularly serious ones such as asthma. Laura did not miscalculate that morning, but she should have been more careful. She should have told someone she was having an attack and should never have walked alone to the hospital.

It is a message I pray everyone who reads this will pass along to the people in their lives who have asthma. A message that Sumita Khatri, MD, an asthma expert and codirector of the Cleveland Clinic Asthma Center, stressed to me when explaining just how quickly asthma can turn fatal: If an attack strikes when you are alone, let someone know.

Because even if you reach the door of a hospital, you might not get in.

After the full version of this story appeared on bostonglobe.com, hospital leaders apologized and acknowledged that mistakes had cost Laura her life.

Today, when you approach the front of Somerville Hospital, the entrance that Laura found locked is the main public doorway to the emergency room. There’s a large illuminated “Emergency” sign above it, as well as several additional signs on the property pointing patients to use that entrance, which is never locked. The bench where Laura collapsed is now bathed in bright light at night, and security cameras are always monitored.

Peter DeMarco continues to advocate for change, pushing 911 administrators to retrain operators and filing legislation—“Laura’s Law”—to create standards for hospitals requiring signage, lighting, and the monitoring of doors. Through the Asthma and Allergy Foundation of America, he has sought to bring attention to Asthma Peak Week, when common triggers are at their highest levels. It strikes the third week in September—the week Laura had her attack. And he established the Lift4Laura Foundation to fund personal gym training sessions for underprivileged and abused women in his wife’s memory.

To read the full-length article, visit the Boston Globe website.