How One Woman’s Pursuit of Healthy Bread Paved The Way For Pepperidge Farm

Updated: Jul. 14, 2023

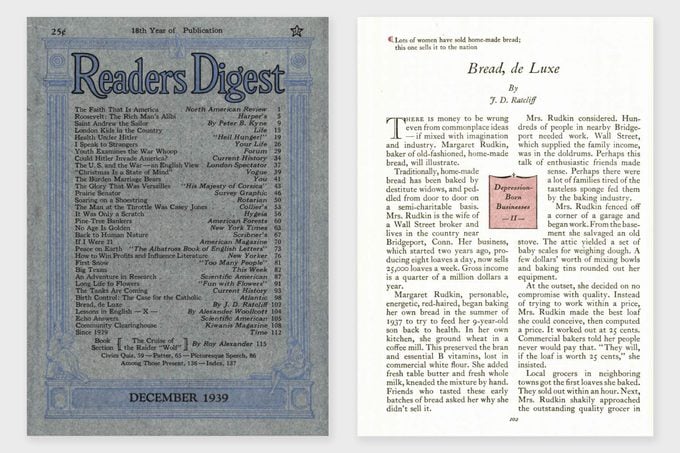

Originally published in December of 1939, this RD classic highlights a depression-born bread making business—and the woman behind it.

In honor of the 100th anniversary of Reader’s Digest, we are looking back at some of our best moments from the past ten decades. Head here for more on our milestone anniversary.

There is money to be wrung even from commonplace ideas—if mixed with imagination and industry. Margaret Rudkin, baker of old-fashioned, homemade bread, will illustrate.

Traditionally, homemade bread has been baked by destitute widows and peddled from door to door on a semi-charitable basis. Mrs. Rudkin is the wife of a Wall Street broker and lives in the country near Bridgeport, Conn. Her business, which started two years ago, producing eight loaves a day, now sells 25,000 loaves a week. Gross income is a quarter of a million dollars a year.

Who is Margaret Rudkin?

Margaret Rudkin—personable, energetic, red-haired—began baking her own bread in the summer of 1937 to try to feed her 9-year-old son back to health. In her own kitchen, she ground wheat in a coffee mill. This preserved the bran and essential B vitamins lost in commercial white flour. She added fresh table butter and fresh whole milk, then kneaded the mixture by hand. Friends who tasted these early batches of bread asked her why she didn’t sell it.

Mrs. Rudkin considered. Hundreds of people in nearby Bridgeport needed work. Wall Street, which supplied the family income, was in the doldrums. Perhaps this talk of enthusiastic friends made sense. Perhaps there were a lot of families tired of the tasteless sponge fed to them by the baking industry.

RELATED: How an Activist with Disabilities Went from Being a Role Model to a Runway Model

Turning an idea into a reality

Mrs. Rudkin fenced off a corner of a garage and began work. From the basement, she salvaged an old stove. The attic yielded a set of baby scales for weighing dough. A few dollars’ worth of mixing bowls and baking tins rounded out her equipment.

At the outset, she decided on no compromise with quality. Instead of trying to work within a price, Mrs. Rudkin made the best loaf she could conceive, then computed a price. It worked out to 25 cents. Commercial bakers told her people never would pay that. “They will, if the loaf is worth 25 cents,” she insisted.

Local grocers in neighboring towns got the first loaves she baked. They sold out within an hour. Next, Mrs. Rudkin shakily approached the outstanding quality grocer in New York. The manager cut her sales talk short and asked for a slice of the bread. It was the best he had tasted since he was a boy, he said. He started off with a dozen loaves a day. Within a few months, this order grew to 200 daily.

Meanwhile, the growing bakery overflowed from the garage into a nearby stable. Makeshift equipment gave way to professional ovens, and local employment boomed. Mrs. Rudkin contracted to use the entire facilities of first one, then two Connecticut mills—supplying her own top-grade wheat, bought in Minneapolis, now at the rate of a carload (42,000 pounds) every ten days.

But as business grew, Mrs. Rudkin made no concession to mass-production methods. The bread was still kneaded by hand, flavored with pure honey (she used a ton a week), mixed with the best milk—the total output of a local dairy. It was set to rise in a room where humidity was supplied by a teakettle boiling on a one-burner stove. The prime qualification of 28 young women hired was that they should know nothing about making bread. Mrs. Rudkin wanted to be sure they’d do it entirely her way.

She had no paid advertising, but doctors gave an initial push by recommending the bread to patients. Aside from that, word-of-mouth praise from one purchaser to another pushed sales upward, at the rate of 1,000 more loaves a month.

Pepperidge Farm Bread

Through leaflets occasionally packed with the bread, Mrs. Rudkin announced new products as they were added—water-ground corn meal, oatmeal, buckwheat, cracked wheat, and Melba toast made from stale loaves returned by grocers. Her most astonishing leaflet announced that the loaf size was being increased from 22 to 24 ounces. Increased sales had resulted in a saving, passed along in this way to the consumer.

Pepperidge Farm Bread—named for the Rudkin estate—now goes out through ten distributors ranged between Boston and Washington. Four shiny trucks cart it to 250 grocers; it is mailed to 400 individual customers all over the United States. For example, an order from Madison, Wisconsin, for one trial loaf led to orders for 150 loaves a week. Rudkin bread has even ridden the Clipper to Europe to please a customer on vacation.

This home-baked bread industry has presented the local community with a thriving business, 45 new jobs, and an annual payroll in excess of $50,000. Born in a Depression summer, when most people were thinking of retrenchment rather than expansion, conducted by a woman without previous business experience, it illustrates what wit and intelligence can do with an old idea.

Next, read up on how these women who catch pythons in the Everglades turned their own idea into a reality.