A Writer’s Desperate Plea Paints a Horrifying Picture of What Really Happens in a Car Crash

Updated: Apr. 22, 2022

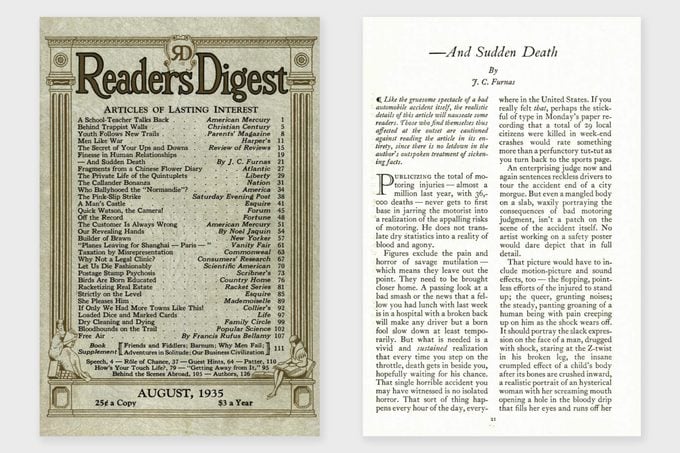

Originally published in August 1935, this Reader's Digest classic aimed to curb reckless driving in order to make the roads just a little bit safer.

In honor of Reader’s Digest‘s 100th anniversary, we are looking back at some of our best moments from the past ten decades. Head here for more on our milestone anniversary. Then keep reading for a gripping piece from the archives, appearing below exactly as it was written 87 years ago.

August 1935

Like the gruesome spectacle of a bad automobile accident itself, the realistic details of this article will nauseate some readers. Those who find themselves thus affected at the outset are cautioned against reading the article in its entirety since there is no letdown in the author’s outspoken treatment of sickening facts.

Publicizing the total of motoring injuries—almost a million last year, with 36 thousand deaths—never gets to first base in jarring the motorist into a realization of the appalling risks of motoring. He does not translate dry statistics into a reality of blood and agony.

Figures exclude the pain and horror of savage mutilation—which means they leave out the point. They need to be brought closer home. A passing look at a bad smash or the news that a fellow you had lunch with last week is in a hospital with a broken back will make any driver but a born fool slow down at least temporarily. But what is needed is a vivid and sustained realization that every time you step on the throttle, death gets in beside you, hopefully waiting for his chance. That single horrible accident you may have witnessed is no isolated horror. That sort of thing happens every hour of the day, everywhere in the United States. If you really felt that, perhaps the stickful of type in Monday’s paper recording that a total of 29 local citizens were killed in weekend crashes would rate something more than a perfunctory tut-tut as you turn back to the sports page.

An enterprising judge now and again sentences reckless drivers to tour the accident end of a city morgue. But even a mangled body on a slab, waxily portraying the consequences of bad motoring judgment, isn’t a patch on the scene of the accident itself. No artist working on a safety poster would dare depict that in full detail.

That picture would have to include motion-picture and sound effects, too—the flopping, pointless efforts of the injured to stand up; the queer, grunting noises; the steady, panting groaning of a human being with pain creeping up on him as the shock wears off. It should portray the slack expression on the face of a man, drugged with shock, staring at the Z-twist in his broken leg, the insane crumpled effect of a child’s body after its bones are crushed inward, a realistic portrait of a hysterical woman with her screaming mouth opening a hole in the bloody drip that fills her eyes and runs off her chin. Minor details would include the raw ends of bones protruding through flesh in compound fractures and the dark red, oozing surfaces where clothes and skin were flayed off at once.

Those are all standard, everyday sequels to the modern passion for going places in a hurry and taking a chance or two by the way. If ghosts could be put to a useful purpose, every bad stretch of road in the United States would greet the oncoming motorist with groans and screams and the educational spectacle of ten or a dozen corpses, all sizes, sexes, and ages, lying horribly still on the bloody grass.

A tragic accident

Last year a state trooper of my acquaintance stopped a big red Hispano [Suiza] for speeding. Papa was obviously a responsible person, obviously set for a pleasant weekend with his family, so the officer cut into Papa’s well-bred expostulations: “I’ll let you off this time, but if you keep on this way, you won’t last long. Get going—but take it easier.”

Later a passing motorist hailed the trooper and asked if the red Hispano had got a ticket. “No,” said the trooper, “I hated to spoil their party.”

“Too bad you didn’t,” said the motorist, “I saw you stop them—and then I passed that car again 50 miles up the line. It still makes me feel sick at my stomach. The car was all folded up like an accordion—the color was about all there was left. They were all dead but one of the kids—and he wasn’t going to live to the hospital.”

Maybe it will make you sick at your stomach too. But unless you’re a heavy-footed incurable, a good look at the picture the artist wouldn’t dare paint, a first-hand acquaintance with the results of mixing gasoline with speed and bad judgment, ought to be well worth your while. I can’t help it if the facts are revolting. If you have the nerve to drive fast and take chances, you ought to have the nerve to take the appropriate cure. You can’t ride an ambulance or watch the doctor working on the victim in the hospital, but you can read.

Brace yourselves against the laws of momentum

The automobile is treacherous, just as a cat is. It is tragically difficult to realize that it can become the deadliest missile. As enthusiasts tell you, it makes 65 feel like nothing at all. But 65 an hour is 100 feet a second, a speed which puts a viciously unjustified responsibility on brakes and human reflexes and can instantly turn this docile luxury into a mad bull elephant.

Collision, turnover, or sideswipe, each type of accident produces, either a shattering dead stop or a crashing change of direction—and since the occupant—meaning you—continues in the old direction at the original speed, every surface and angle of the car’s interior immediately becomes a battering, tearing projectile aimed squarely at you—inescapable. There is no bracing yourself against these imperative laws of momentum.

It’s like going over Niagara Falls in a steel barrel full of railroad spikes. The best thing that can happen to you—and one of the rarer things—is to be thrown out as the doors spring open, so you have only the ground to reckon with. True, you strike with as much force as if you had been thrown from the Twentieth Century at top speed. But at least you are spared the lethal array of gleaming metal knobs and edges and glass inside the car.

Anything can happen in that split second of crash, even those lucky escapes you hear about. People have dived through windshields and come out with only superficial scratches. They have run cars together head on, reducing both to twisted junk and been found unhurt and arguing bitterly two minutes afterward. But death was there just the same—he was only exercising his privilege of being erratic. This spring a wrecking crew pried the door off a car which had been overturned down an embankment, and out stepped the driver with only a scratch on his cheek. But his mother was still inside, a splinter of wood from the top driven four inches into her brain as a result of her son’s taking a greasy curve a little too fast. No blood—no horribly twisted bones—just a gray-haired corpse still clutching her pocketbook in her lap as she had clutched it when she felt the car leave the road.

On that same curve a month later, a light touring car crashed into a tree. In the middle of the front seat they found a 9-months-old baby surrounded by broken glass and yet absolutely unhurt. A fine practical joke on death—but spoiled by the baby’s parents, still sitting on each side of him, instantly killed by shattering their skulls on the dashboard.

If you customarily pass without clear vision a long way ahead, make sure that every member of the party carries identification papers—it’s difficult to identify a body with its whole face bashed in or torn off. The driver is death’s favorite target. If the steering wheel holds together, it ruptures his liver or spleen so he bleeds to death internally. Or, if the steering wheel breaks off, the matter is settled instantly by the steering column’s plunging through his abdomen.

A modern death-trap

By no means do all head-on collisions occur on curves. The modern death-trap is likely to be a straight stretch with three lanes of traffic—like the notorious Astor Flats on the Albany Post Road where there have been as many as 27 fatalities in one summer month. This sudden vision of broad, straight road tempts many an ordinarily sensible driver into passing the man ahead. Simultaneously a driver coming the other way swings out at high speed. At the last moment, each tries to get into line again, but the gaps are closed. As the cars in line are forced into the ditch to capsize or crash fences, the passers meet, almost head on, in a swirling, grinding smash that sends them caroming obliquely into the others.

A trooper described such an accident—five cars in one mess, seven killed on the spot, two dead on the way to the hospital, two more dead in the long run. He remembered it far more vividly than he wanted to—the quick way the doctor turned away from a dead man to check up on a woman with a broken back; the three bodies out of one car so soaked with oil from the crankcase that they looked like wet brown cigars and not human at all; a man, walking around and babbling to himself, oblivious of the dead and dying, even oblivious of the dagger-like sliver of steel that stuck out of his streaming wrist; a pretty girl with her forehead laid open, trying hopelessly to crawl out of a ditch in spite of her smashed hip. A first class massacre of that sort is only a question of scale and numbers—seven corpses are no deader than one. Each shattered man, woman, or child who went to make up the 36,000 corpses chalked up last year had to die a personal death.

A car careening and rolling down a bank, battering and smashing its occupants every inch of the way, can wrap itself so thoroughly around a tree that front and rear bumpers interlock, requiring an acetylene torch to cut them apart. In a recent case of that sort, they found the old lady, who had been sitting in back, lying across the lap of her daughter, who was in front, each soaked in her own and the other’s blood; distinguishably, each so shattered and broken that there was no point whatever in an autopsy to determine whether it was broken neck or ruptured heart that caused death.

Overturning cars specialize in certain injuries. Cracked pelvis, for instance, guaranteeing agonizing months in bed, motionless, perhaps crippled for life—broken spine resulting from sheer sidewise twist—the minor details of smashed knees and splintered shoulder blades caused by crashing into the side of the car as she goes over with the swirl of an insane roller coaster—and the lethal consequences of broken ribs, which puncture hearts and lungs with their raw ends. The consequent internal hemorrhage is no less dangerous because it is the pleura instead of the abdominal cavity that is filling with blood.

Flying glass—safety glass is by no means universal yet—contributes much more than its share to the spectacular side of accidents. It doesn’t merely cut—the fragments are driven in as if a cannon loaded with broken bottles had been fired in your face, and a sliver in the eye, traveling with such force, means certain blindness. A leg or arm stuck through the windshield will cut clean to the bone through vein, artery, and muscle like a piece of beef under the butcher’s knife, and it takes little time to lose a fatal amount of blood under such circumstances. Even safety glass may not be wholly safe when the car crashes something at high speed. You hear picturesque tales of how a flying human body will make a neat hole in the stuff with its head—the shoulders stick, the glass holds, and the raw, keen edge of the hole decapitates the body as neatly as a guillotine.

Or, to continue with the decapitation motif, going off the road into a post-and-rail fence can put you beyond worrying about other injuries immediately when a rail comes through the windshield and tears off your head with its splintery end—not as neat a job but thoroughly efficient. Bodies are often found with their shoes off and their feet all broken out of shape. The shoes are back on the floor of the car, empty and with their laces still neatly tied. That is the kind of impact produced by modern speeds.

Gambling with a sudden death

But all that is routine in every American community. To be remembered individually by doctors and policemen, you have to do something as grotesque as the lady who burst the windshield with her head, splashing splinters all over the other occupants of the car, and then, as the car rolled over, rolled with it down the edge of the windshield frame and cut her throat from ear to ear. Or park on the pavement too near a curve at night and stand in front of the tail light as you take off the spare tire—which will immortalize you in somebody’s memory as the fellow who was mashed three feet broad and two inches thick by the impact of a heavy-duty truck against the rear of his own car. Or be as original as the pair of youths who were thrown out of an open roadster this spring—thrown clear—but each broke a windshield post with his head in passing and the whole top of each skull, down to the eyebrows, was missing. Or snap off a nine-inch tree and get yourself impaled by a ragged branch.

None of all that is scare-fiction; it is just the horrible raw material of the year’s statistics as seen in the ordinary course of duty by policemen and doctors, picked at random. The surprising thing is that there is so little dissimilarity in the stories they tell.

It’s hard to find a surviving accident victim who can bear to talk. After you come to, the gnawing, searing pain throughout your body is accounted for by learning that you have both collarbones smashed, both shoulder blades splintered, your right arm broken in three places and three ribs cracked, with every chance of bad internal ruptures. But the pain can’t distract you, as the shock begins to wear off, from realizing that you are probably on your way out. You can’t forget that, not even when they shift you from the ground to the stretcher and your broken ribs bite into your lungs and the sharp ends of your collarbones slide over to stab deep into each side of your screaming throat. When you’ve stopped screaming, it all comes back you’re dying and you hate yourself for it. That isn’t fiction either. It’s what it actually feels like to be one of that 36,000.

And every time you pass on a blind curve, every time you hit it up on a slippery road, every time you step on it harder than your reflexes will safely take, every time you drive with your reactions slowed down by a drink or two, every time you follow the man ahead too closely, you’re gambling a few seconds against this kind of blood and agony and sudden death.

Take a look at yourself as the man in the white jacket shakes his head over you, tells the boys with the stretcher not to bother, and turns away to somebody else who isn’t quite dead yet. And then take it easy.

Next, learn how to handle these scary driving scenarios.