What Overturning Roe v. Wade Could Mean for the United States

Updated: Jan. 17, 2024

What could the end of Roe v. Wade mean for women's health, civil rights, and American politics?

The Reader’s Digest Version:

|

On June 24, 2022, the Supreme Court overturned the notoriously controversial case of Roe v. Wade, which legalized abortion. This came nearly two months after a leaked draft of a Supreme Court opinion suggested this ruling could be imminent. The justices voted along strict ideological lines, 6–3, with Justice Samuel Alito writing in the majority opinion that “the Constitution makes no reference to abortion, and no such right is implicitly protected by any constitutional provision, including the one on which the defenders of Roe and Casey now chiefly rely.” Since that provision is not “deeply rooted in this Nation’s history and tradition” or “implicit in the concept of ordered liberty,” he continues, the states should have the final say over abortion laws.

Justices Stephen Breyer, Sonia Sotomayor, and Elena Kagan denounced the idea of “forced childbirth” in their dissent, adding that today’s Supreme Court “does not think there is anything of constitutional significance attached to a woman’s control of her body and the path of her life.” In closing, they wrote: “With sorrow—for this Court, but more, for the many millions of American women who have today lost a fundamental constitutional protection—we dissent.”

The issue has been divisive for 50 years, both for the Supreme Court—with its changing roster of nine justices, each with a lifetime appointment and not answerable to voters—as well as politicians and the public. Even “Jane Roe” was an activist on both sides of it during her life. But what does overturning Roe v. Wade mean, exactly? And now that the federally protected right to abortion has disappeared, what are the implications for women’s health, American politics, and other privacy-based rights? Constitutional law scholars, public health experts, political scientists, and health care providers all agree: The ripple effects may be felt far and wide.

What did Roe v. Wade really decide?

Roe v. Wade is one of the most divisive opinions in the history of the Supreme Court. Decided in 1973, it held that the Ninth and Fourteenth Amendments to the U.S. Constitution protect the individual right of privacy, and included in one’s privacy is the right to choose to have an abortion.

The case was brought by Norma McCorvey, a Texas woman who was pregnant and didn’t want to be. At the time, Texas law permitted abortion only in cases of rape, incest, and to protect the life of the mother. Two young lawyers, Sarah Weddington and Linda Coffee, took on McCorvey’s case, giving her the pseudonym “Jane Roe” to protect her identity and naming Dallas District Attorney Henry Wade as the defendant. The district court would agree with McCorvey’s attorneys and find that the Texas law denied her right to privacy under the Constitution.

Weddington argued that the case was a test of whether all Americans had the right to determine the course of their lives. Like questions of marriage, procreation, and child-rearing, which the Court had already said were of such a personal nature that the state couldn’t interfere, she added, “there are certain things that are so much a part of the individual concern that they should be left to the determination of the individual.”

The nine men of the black-robed Court (Sandra Day O’Connor wouldn’t become the first woman to serve on the nation’s highest court until 1981) eventually decided by a 7–2 vote that the Constitution recognizes the right to privacy, encompassing abortion, and that the state cannot interfere with it before the fetus reaches “viability” (its ability to survive outside the womb) at about 24 to 28 weeks of gestation.

How did Roe v. Wade affect America?

Roe‘s effect on women’s health was immediate. A report by the Centers for Disease Control found that unsafe, illegal abortions in 1972—the year before Roe—totaled about 130,000. By 1974, the number dropped to 17,000. Deaths from botched illegal abortions in the same period fell from 39 to five.

The decision also became a political ignition point. Activists on both sides of the issue—those who say the life of the fetus must be protected versus those who believe it is a private, personal, moral, and medical decision for a woman and her doctor—have rallied around it for nearly 50 years. The Supreme Court has spent the past five decades defining what the right to abortion is and how the states may regulate it without infringing on women’s rights to bodily integrity and privacy.

Why wasn’t the right to abortion absolute?

Rights are rarely absolute. The government may limit and regulate those rights if it can show a compelling state interest that overrides the individual’s right. For example, even though the Second Amendment guarantees the people’s right to bear arms, you can’t keep a bazooka in your home because the threat to public safety from such a powerful weapon outweighs your individual right.

The Roe decision presented similar restrictions on abortion, based on the viability of the fetus. Under Roe, the government had no authority to regulate abortions in the first trimester. During the second trimester, regulations were allowed for “reasonable” purposes related to the health of the mother. By the third trimester, the state had an interest in preserving the potential life in the womb and could regulate or prohibit abortions in the interests of the life of the fetus or the mother.

The Roe decision has been revisited many times over the years, and while specific regulations and restrictions have been permitted, the underlying right to abortion was not overturned. In 1992, the Court ruled in Planned Parenthood v. Casey that the right to abortion was subject to state regulation, as long as the restrictions did not “unduly burden” the woman seeking the abortion. Among the regulations determined not to be an undue burden were waiting periods, mandatory counseling, parental consent, and mandatory submission to ultrasounds that make the fetus visible and audible to the mother.

What is happening with Roe v. Wade right now?

With the Supreme Court’s ruling on June 24, the constitutional right to abortion has disappeared on a federal level. In early May, Politico published a leaked draft of an opinion in the case of Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, indicating that it would overturn Roe. The draft, written by Justice Samuel Alito, said that “Roe was egregiously wrong from the start.”

“Roe‘s defenders characterize the abortion right as similar to the rights recognized in past decisions involving matters such as intimate sexual relations, contraception, and marriage, but abortion is fundamentally different,” Alito wrote, “because it destroys what those decisions called ‘fetal life’ and what the law now before us describes as an ‘unborn human being.'” The opinion went on to recommend that the matter revert to the states to decide, and noted that “women are not without electoral or political power” and may exercise that power at the ballot box to determine whether abortion remains legal in their state.

When it was released, the opinion caused howls of rage from reproductive-rights supporters as well as whoops of joy from anti-abortion activists. Though Chief Justice John Roberts issued a statement confirming that the leaked document was genuine, he also said it was not a final decision of the Court or necessarily the final position of any of its justices, though it did end up being the basis of the Supreme Court’s ultimate decision. At the time, Roberts also pledged to find the source of the leak and hold them accountable. Experts say that such a leak is not a crime, but it does diverge sharply from the traditions of the secrecy that usually guards Supreme Court deliberations.

Who leaked the draft?

No one knows for sure who leaked the draft. It could have come from liberals to spur outrage and perhaps change opinions before the Court announced its conclusion, or it might have come from conservatives trying to lock justices into their votes before they could change their minds. Another theory posits that the leak was orchestrated by Chief Justice John Roberts himself to shift attention to the leak and away from the decision itself.

Regardless of who leaked the draft, abortion-rights advocates took it at face value and expected that this constitutional right would soon disappear.

What could happen now that Roe v. Wade has been overturned?

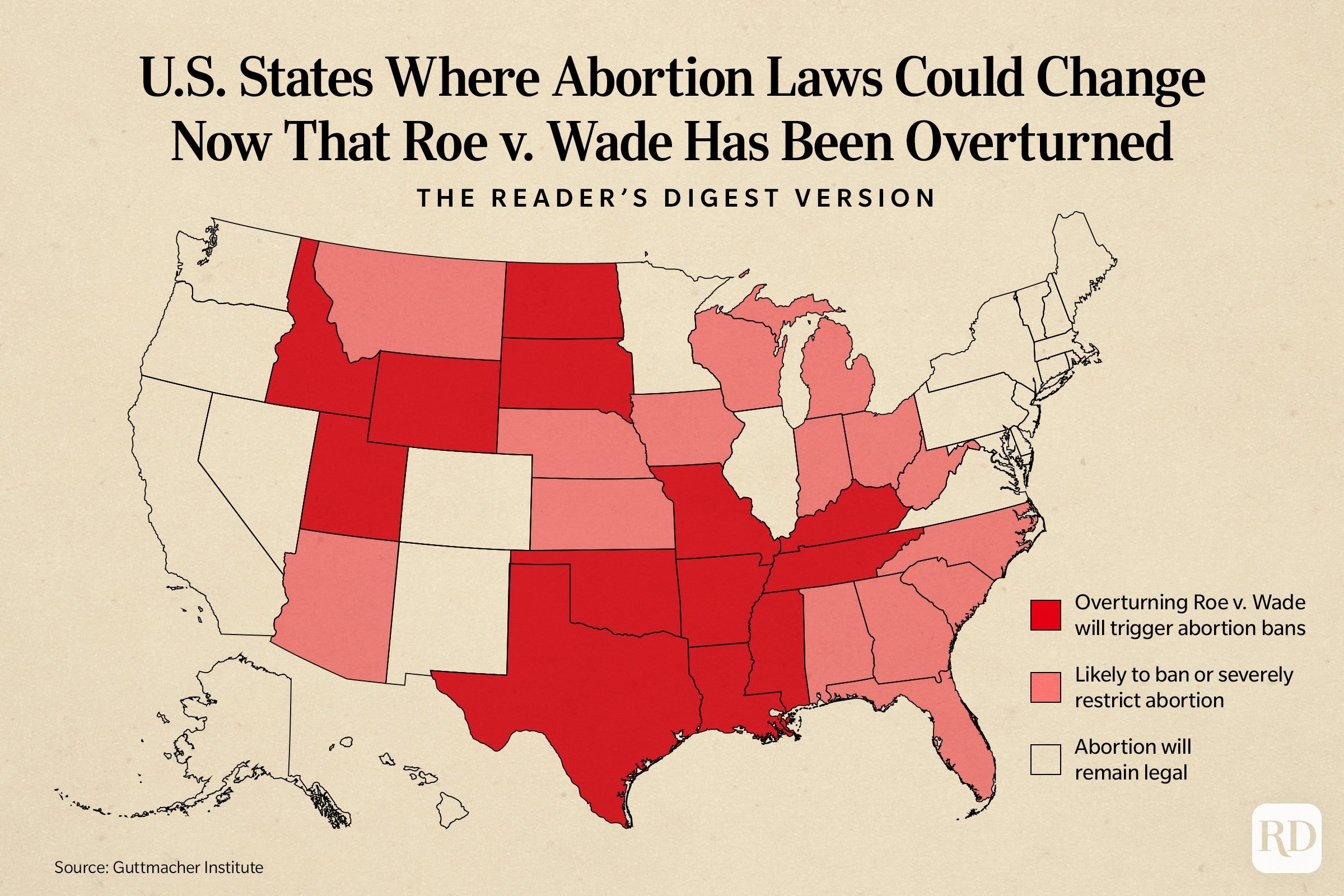

According to the Guttmacher Institute, more than 23 states already have laws on the books banning abortion that are either not enforced or would not become effective until Roe was overturned. Conversely, 16 states already have laws that guarantee abortion rights in all or most circumstances. So, what will happen now that Roe has been overturned?

“In the state of Alabama, it’s more a question of what happens literally the next minute after Roe is overturned,” says Robin Marty, communications director of the West Alabama Women’s Center and author of Handbook for a Post-Roe America. Alabama, Marty explains, has a law already on the books that becomes effective and enforceable immediately upon Roe being overruled. “As soon as that opinion comes out, any abortion for any reason, becomes illegal. Every patient in the waiting room, everyone who’s in the nurses’ room getting counseling, even if they’ve got a cup of water in their hand ready to take a pill, even a patient who’s undressed and waiting on an exam table…they all have to go home. We can’t treat them at that point.”

Many other states have laws that will go into effect within days or weeks, while others have indicated that their legislatures will pass or activate laws banning or severely restricting abortion. North Dakota governor Kristi Noem, for example, has pledged to call the legislature into special session to immediately pass a law guaranteeing a “right to life” for every fetus in that state. In April, a state legislator in Missouri proposed criminalizing traveling to another state to get an abortion, in a first-of-its-kind bill.

Other states, however, will attempt to pass new laws protecting abortion rights. This is currently under discussion in Wisconsin. If successful, Wisconsin would join 16 other states and the District of Columbia in codifying the right to an abortion. Not sure what codify means? Neither did thousands of others, as it became one of 2022’s Merriam Webster’s words of the year. For now, at least, even though Roe v. Wade has been overturned, abortion will not be outlawed on a federal level.

How will overturning Roe v. Wade affect women’s health?

The most pressing practical effect is on women’s reproductive health. The World Health Organization (WHO) recently released an advisory statement and guidelines recommending more open abortion laws across the globe, “in a bid to protect the health of women and girls and help prevent over 25 million unsafe abortions that currently occur each year.” The WHO goes on to state that restricting access to abortions does not actually reduce the number of abortions that take place—it only makes women and girls seek other abortion options that are often unsafe: “In countries where abortion is most restricted, only 1 in 4 abortions are safe, compared to nearly 9 in 10 in countries where the procedure is broadly legal.”

Marty agrees that abortion will still occur in the United States, but she says that women’s lives won’t necessarily be in as much jeopardy as they were in pre-Roe America. “The difference is now we have the medical knowledge and means to get a safe, medically induced abortion in the form of a pill,” she says, noting that online pharmacies are already available and will provide abortifacient drugs. However, those drugs might not come from a reputable pharmacy or might not arrive in time to be effective. At which point, Marty says, “a person who wants an abortion and can’t get one will do desperate things.”

Pregnant people could be denied lifesaving treatment

There are times when pregnancy can endanger a woman’s life. What does overturning Roe v. Wade mean for women in these situations? Very simply, it means they may not receive lifesaving treatment. That happened in Ireland in 2012 to Savita Halappanavar, who began miscarrying in her 17th week of pregnancy. Even though she was in medical distress and the pregnancy couldn’t be saved, doctors refused to perform an abortion because it was illegal in the country at that time. Halappanavar subsequently died of sepsis, a blood infection.

Similar issues can arise with ectopic pregnancies, in which an embryo grows in a fallopian tube and eventually causes it to rupture, and with missed miscarriages, in which the body doesn’t expel a fetus that is no longer alive. Abortion procedures are currently used in both of these cases, but overturning Roe could make them illegal in some states.

Patients could face criminal charges

While many states’ abortion laws do not target the mothers, others do. In April, 26-year-old Texas woman Lizette Herrera was arrested and charged with murder for allegedly inducing her own miscarriage, though the public outcry against the prosecution ultimately led to her release from jail without charges. (A law proposed last year would have subjected Herrera to the death penalty.) The Louisiana legislature recently advanced a law to include abortion under its definition of homicide, which could bring murder charges to any doctor, nurse, or patient involved in an abortion.

The National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers (NACDL) issued a report in 2021 warning of a tidal wave of criminal prosecutions of both abortion providers and patients in the wake of Roe‘s demise. “The Report outlines the many existing state laws used to police the behavior of pregnant women and prosecute them for pregnancy outcomes,” the NACDL wrote in a press release.

According to the Mayo Clinic, 10 to 20 percent of pregnancies end naturally in miscarriage, while the CDC says one in 160 pregnancies ends in stillbirth. In some states, those cases could be referred for criminal prosecution. While these cases often arise in the “Bible Belt” of the South, others have emerged in Utah, Indiana, California, and Iowa.

Volunteers are taking steps to make sure abortion remains available

“Health care for women will vary vastly on the basis of where you live, in a way we’ve never seen before,” says political commentator Carolyn Fiddler. “We’re already starting to see people take action.”

Some of that action is occurring in the political arena, while other efforts are taking a more practical, hands-on approach. The Atlantic recently reported on a group of women training one another on “menstrual extraction,” a process using a simple hand-operated vacuum pump to remove the uterine lining. It can be used to accelerate menstruation; it can also be used to remove a fetus early in a pregnancy.

Other groups are focused on getting those seeking abortions to places where they can access abortions. The Reddit community “r/auntienetwork,” which has seen fast growth since it started in May 2019, helps women who live in places where the law, economics, and geography limit their choices. “Aunties” have opened their homes and provided transportation for women from places like Texas, where recent laws have restricted access to abortions and imposed severe penalties against those who run afoul of the law, or any of the estimated 90 percent of American counties without reproductive health care facilities.

This decision could exacerbate inequality

A common critique of the state-by-state approach to abortion regulation is that it penalizes the poor, who lack the resources to travel out of state to obtain a legal abortion. A Washington Post report found a strong correlation between restrictive abortion laws and women with low incomes, women without health insurance, and maternal death. The NACDL report also found that abortion-related criminal cases primarily target poor and minority women.

“Women of means will always be able to go to a state where abortion is safe and legal. Women without means will be stuck,” says Fiddler, adding that the choice will be between compelled pregnancy and its out-of-pocket costs and lost earning power, and a potentially unsafe, illegal abortion. “Abortions will happen, legal or not, and some women may die.”

Now that Roe v. Wade has been overturned, what other rights might be overturned next?

Roe v. Wade was one in a continuum of Supreme Court cases that recognized and expanded fundamental rights that were not specifically named in the Constitution but were nonetheless cherished individual liberties. Those rights, like whom you marry, whether you have children, and how you raise your children, are of such a personal and intimate nature that the government has no business telling you what to do unless it has a powerful reason to do so (in cases of underage marriage or child abuse, for example).

But those rights are not written anywhere in the U.S. Constitution. Rather, they are created by “penumbras, formed by emanations” of the other rights enumerated in the text of the Bill of Rights. That curious phrase, written by Justice William O. Douglas in his majority opinion in Griswold v. Connecticut, stood for the idea that the many rights the Constitution expressly grants to the people—the Third Amendment freedom from being forced to house soldiers, and the Fourth Amendment freedom from intrusion into their homes and personal effects without a warrant, for example—create a zone of privacy where the government cannot intrude without a compelling state interest. From those specific liberties, Douglas reasoned that even though it is not specified in the Constitution, privacy is one of the core rights Americans possess.

Here are the other privacy-related rights that could be infringed upon now that Roe has been overturned.

Contraceptive use

Griswold held, in 1965, that married couples had a right to buy and use contraceptives as part of their private lives, and the state had no authority to interfere in such an intimate matter. As the first case to hold that the Constitution protects the right to privacy even though it doesn’t expressly say so, it also set the bar for privacy cases that would follow. In 1972, contraceptive care was made legal for unmarried people in Eisenstadt v. Baird.

Pro-life absolutists who believe life begins at the moment of conception object to some methods of birth control. While condoms, diaphragms, and similar barrier devices prevent sperm and egg from meeting, other methods, such as IUDs and morning-after pills, prevent fertilized eggs from implanting in the uterine wall and gestating. Abortion opponents claim these latter methods are just abortion by another means, which physicians strongly deny, asserting that pregnancy doesn’t occur until the egg is implanted.

Same-sex marriage

Same-sex couples faced a crushing blow in 1986, when Bowers v. Hardwick upheld a Texas law criminalizing “sodomy,” but were freed from that ruling in 2003, when Lawrence v. Texas overturned the same law, granting sexual autonomy to consenting adults acting in private. Their rights were furthered recognized in 2015’s Obergefell v. Hodges, which ruled that the Fourteenth Amendment’s Equal Protection Clause included the right for same-sex couples to marry. A quick about-face on an important issue is unusual in Supreme Court history, and it perhaps provided a justification to revisit the question, where the “deeply held tradition” standard expressed in the Dobbs draft could be brought to the discussion.

If that occurs, some of the justices making up the Obergefell minority could now be in the majority, putting the ruling at serious risk. In withering dissents of Obergefell, three still-sitting justices—John Roberts, Samuel Alito, and Clarence Thomas—expressed hostility to the result on “traditional” terms similar to those expressed in the Dobbs draft. Roberts wrote, “The Court today not only overlooks our country’s entire history and tradition but actively repudiates it, preferring to live only in the heady days of the here and now.”

Interracial marriage

In 1967, Loving v. Virginia held that states could not prevent interracial marriages, finding that so-called “anti-miscegenation” laws served no legitimate state purpose to justify their intrusion on the intimate, personal freedom to marry. One U.S. senator, Indiana Republican Mike Braun, recently suggested that interracial marriage is a matter that should be decided by the states, criticizing Loving as an example of judicial activism. Braun quickly withdrew the claim and denounced racism when his comment sparked outrage.

Why these civil rights concerns aren’t far-fetched

For scholars and advocates for marginalized communities, this is cause for alarm. David Cruz, a professor of Constitutional Law at the University of Southern California, says the leaked opinion was “deeply skeptical about the protection of any rights not specifically spelled out in the text of the Constitution” and “claims that it adheres to the Court’s longstanding acceptance of interpreting the Constitution to protect unenumerated rights deeply rooted in U.S. legal history and tradition.”

Cruz says “traditions” are not concrete and distinct things. Instead, they are subject to different interpretations and frames, and that leaves them vulnerable to the whims of a particular judge’s biases. For example, the right to marry a person of the same sex is not a longstanding tradition in American law, but the right to marry is. A judge who is hostile to LGBTQ rights could use “tradition” to uphold his or her bias.

“There are two key problems with the ‘traditions and history’ angle,” says University of Miami law professor Caroline Mala Corbin. “First, there is no single definition of what ‘history’ is. It’s malleable, vague, and complex, and it’s susceptible to cherry-picking” by those who look for justification for the results they seek, rather than looking for guidance and clarification. Corbin’s second problem echoes Cruz’s concern: A “tradition” can be framed narrowly or broadly, and that frame can determine whether a right is “traditional” or not.

Corbin also adds a third problem: “Why should we look to history and tradition when we know that throughout our history, the law has been racist, sexist, and homophobic?” she asks.

Cases that bucked historic racism, sexism, and homophobia, like Loving, Lawrence, and Obergefell, could be overruled using the same logic found in the leaked Dobbs draft. “All of these legal rights would be vulnerable if the draft or something close to it becomes the opinion of the Court,” Cruz says.

Corbin agrees. “Realistically, I don’t think any court has the stomach to overturn Brown v. Board of Education [which ended legal segregation] or Loving. But I don’t have the same sense of security regarding LGBTQ rights,” she says. “Many judges have already expressed hostility to those rights, and the blueprint to overturn them is right there in the draft opinion. And those cases aren’t 50 years old (like Roe).”

How will the Roe v. Wade reversal affect the political landscape?

Roe v. Wade has been a convenient litmus test on both sides of the political fence for nearly 50 years. Whether a candidate was firmly “pro-life” or staunchly “pro-choice” was a good predictor of their likely success in climbing their party’s power structure. But now that Roe has been overturned before this fall’s midterm election, experts see a shake-up coming that neither side predicted.

“The path forward has largely turned to what abortion opponents can do now that they got the result they’ve campaigned on for the past 50 years,” says Fiddler, “and whether abortion rights supporters can coalesce around this issue and get people to the polls.” Since conservatives have promised for so long to overturn Roe v. Wade, they may be victims of their own success and lose some of their most reliable voters. At the same time, moderate and liberal voters may be motivated to vote in the November midterms, especially since there has also been talk of a federal abortion ban. It is also important to remember that nearly two thirds of Americans support at least some access to abortion.

“I’ve talked to a number of younger people who thought this [abortion-rights question] was never going to be an issue for them,” says Sofia Gruskin, professor of law and medicine and director of the Institute on Inequalities in Global Health at the University of Southern California. “You can see it in their faces—they’re motivated to do something about it.”

Democrats have also floated ideas like increasing the number of Supreme Court justices to dilute the power of the conservatives on the bench and writing the right to an abortion into law through the legislative process. While these efforts didn’t actually happen before the June ruling, they likely would have failed, as each would have required ending the filibuster in the Senate, and the likelihood of that was almost nil.

What can I do about Roe v. Wade?

To make your voice heard, contact the members of Congress in your area, as well as your state lawmakers. Whichever side of the debate you’re on, this is an opportunity to influence one of the most important issues in American history. And if the past is a good teacher, the debate will not be going away anytime soon.

Sources:

- Guttmacher Institute: “Abortion Before and After Legalization”

- Oyez: “Roe v. Wade”

- Oyez: “Planned Parenthood of Southeastern Pennsylvania v. Casey”

- Politico: “Read Justice Alito’s initial draft abortion opinion which would overturn Roe v. Wade”

- Guttmacher Institute: “Abortion Policy in the Absence of Roe”

- Robin Marty, communications director of the West Alabama Women’s Center and author of Handbook for a Post-Roe America

- WHO: “WHO issues new guidelines on abortion to help countries deliver lifesaving care”

- The Crime Report: “Abortion, Prison and the Death Penalty”

- Carolyn Fiddler, a political commentator and the author of the “This Week in Statehouse Action” newsletter

- The Atlantic: “The Future of Abortion in a Post-Roe America”

- Politico: “The Supreme Court’s most memorable quotes on gay marriage”

- David Cruz, professor of Constitutional Law at the University of Southern California

- Caroline Mala Corbin, a law professor at University of Miami

- Sofia Gruskin, professor of law and medicine and director of the Institute on Inequalities in Global Health at the University of Southern California